A first-of-its-kind study shows the mouth is a robust site for infection and transmission of COVID-19, according to new research published Oct. 27 on the preprint server medRxiv.

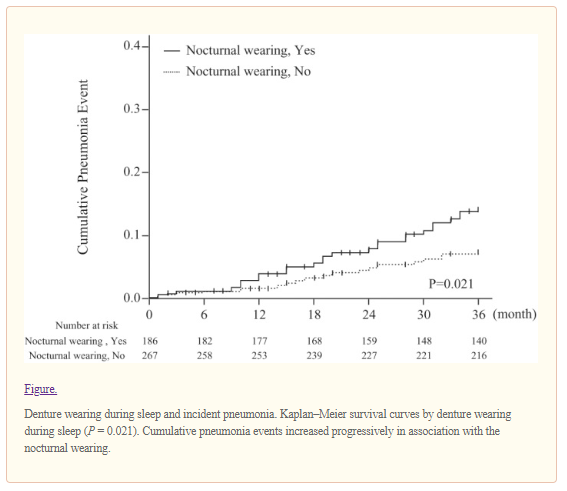

A team of researchers led by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research reveals coronavirus can take hold in the salivary glands where it replicates, and in some cases, leads to prolonged disease when infected saliva is swallowed into the gastrointestinal tract or aspirated to the lungs where it can lead to pneumonia.

While most COVID-19 research has focused on the nose and lungs, this is the first study to identify the mouth as a primary site for coronavirus infection and underscores the importance of wearing a face covering and physical distancing. The results have not been peer-reviewed.

“Our results show oral infection of COVID-19 may be underappreciated,” said senior study author Kevin M. Byrd, research instructor at the UNC-Chapel Hill Adams School of Dentistry and the Anthony R. Volpe Research Scholar at the American Dental Association Science and Research Institute. “Like nasal infection, oral infection could underlie the asymptomatic spread that makes this disease so hard to contain.”

Byrd along with Blake Warner, chief of the Salivary Disorders Unit at the NIDCR, coordinated the research conducted at the National Institutes of Health, Wellcome Sanger Institute, UNC Marsico Lung Institute and the J. Craig Venter Institute.

Researchers are just beginning to explore the oral symptoms patients experience during COVID-19, such as loss of taste or smell and persistent dry mouth.

In the study, researchers report preliminary results from a clinical trial of 40 subjects with COVID-19 which showed sloughed epithelial cells lining the mouth can be infected with SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. The amount of virus in patient saliva was positively correlated with taste and smell changes, according to the study.

Relying on oral cell identity maps, researchers also looked at where in the mouth the virus infects. They surveyed oral tissues with the highest levels of ACE2, the receptor that helps coronavirus grab and invade human cells.

Based on ACE2 expression and analysis of cadaver tissue, the most likely sites of infection in the mouth are the salivary glands, tongue and tonsil, the study showed.

The findings provide more evidence of the role of saliva in COVID-19. COVID-19 infection, specifically in the mouth, can allow the virus to spread internally and to others as the infected person breathes, speaks and coughs.

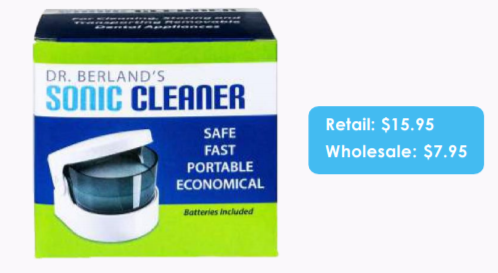

Read our tips on what can Denture and Oral Appliance Wearers do to reduce the risk of developing Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome from Covid-19.

The team of researchers started their investigation early in the pandemic and following six months of collaboration have produced new insights on ways COVID-19 infects the mouth and throat.

Their work has led to the creation of the Oral and Craniofacial Biological Network as part of the Human Cell Atlas. As those in the network work towards the goal of creating comprehensive maps of oral and craniofacial cells as a basis for understanding oral health and oral diseases, they will openly share research findings that may shape the COVID-19 response.

To read more, click here