Denture Wearing during Sleep Doubles the Risk of Pneumonia in the Very Elderly

Dentures, Streptococcus, & Pneumonia

Liquid Crystal From Dr. B Dental Solutions is the only soak cleanser that kills Streptococcus, the pathogen that causes Pneumonia from dentures.

Associated Data

ABSTRACT

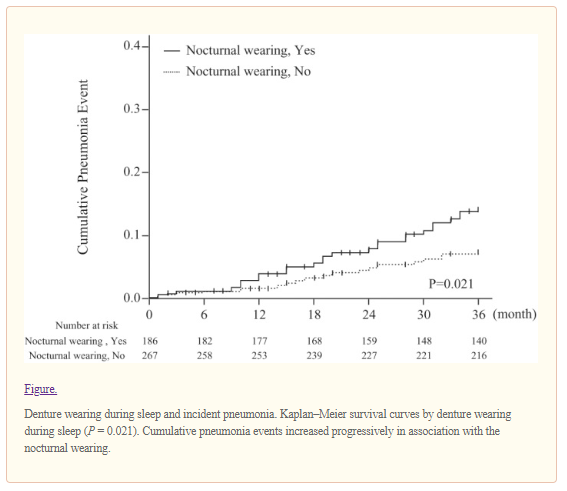

Poor oral health and hygiene are increasingly recognized as major risk factors for pneumonia among the elderly. To identify modifiable oral health–related risk factors, we prospectively investigated associations between a constellation of oral health behaviors and incident pneumonia in the community-living very elderly (i.e., 85 years of age or older). At baseline, 524 randomly selected seniors (228 men and 296 women; mean age, 87.8 years) were examined for oral health status and oral hygiene behaviors as well as medical assessment, including blood chemistry analysis, and followed up annually until first hospitalization for or death from pneumonia. During a 3-year follow-up period, 48 events associated with pneumonia (20 deaths and 28 acute hospitalizations) were identified. Among 453 denture wearers, 186 (40.8%) who wore their dentures during sleep were at higher risk for pneumonia than those who removed their dentures at night (log rank P = 0.021). In a multivariate Cox model, both perceived swallowing difficulties and overnight denture wearing were independently associated with an approximately 2.3-fold higher risk of the incidence of pneumonia (for perceived swallowing difficulties, hazard ratio [HR], 2.31; and 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.11–4.82; and for denture wearing during sleep, HR, 2.38; and 95% CI, 1.25–4.56), which was comparable with the HR attributable to cognitive impairment (HR, 2.15; 95% CI, 1.06–4.34), history of stroke (HR, 2.46; 95% CI, 1.13–5.35), and respiratory disease (HR, 2.25; 95% CI, 1.20–4.23). In addition, those who wore dentures during sleep were more likely to have tongue and denture plaque, gum inflammation, positive culture for Candida albicans, and higher levels of circulating interleukin-6 as compared with their counterparts. This study provided empirical evidence that denture wearing during sleep is associated not only with oral inflammatory and microbial burden but also with incident pneumonia, suggesting potential implications of oral hygiene programs for pneumonia prevention in the community.

INTRODUCTION

Pneumonia is a major morbidity and mortality risk among the elderly. The 2010 Global Burden of Disease Study reported that lower respiratory tract infections, including pneumonia, are the fourth leading cause of death globally, and the second most frequent reason for years of life lost (Lozano et al. 2012). In Japan, pneumonia has ranked as the third leading cause of death since 2011, and the second leading cause of death among nonagenarians (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare 2012). Aspiration is an important pathogenic mechanism for pneumonia in the elderly, and poor oral health is increasingly recognized as a predisposing factor (Janssens and Krause 2004). Indeed, randomized interventional trials demonstrated that professional oral care reduces the burden of pneumonia among the frail elderly in long-term care facilities (Adachi et al. 2002). It remains unknown, however, whether improving oral hygiene by altering behaviors could reduce the risk of pneumonia in community settings. With a rapid demographic shift toward the very elderly in the population and a concomitant increase in the global burden of poor oral condition (Marcenes et al. 2013), the development of a motivational and self-manageable oral health promotion program for pneumonia prevention is a matter of public health priority. To identify behavioral risk factors, modification of which could provide tangible benefits for pneumonia prevention, we prospectively investigated associations between a constellation of oral health behaviors and pneumonia events in the community-living very elderly.

METHODS

Study Population

The Tokyo Oldest Old Survey on Total Health (TOOTH) is an ongoing prospective observational study organized by interdisciplinary experts, including geriatricians, dentists, psychologists, and epidemiologists. Details of its design, its recruitment, and the entire procedure have been described previously (Arai et al. 2010). Between March 2008 and November 2009, we recruited a randomly selected sample of 542 inhabitants of Tokyo aged 85 years or older for medical and dental examination. Among them, 12 subjects were excluded because they lacked oral health assessment, and 6 were excluded because they did not have information on pneumonia incidence; thus, 524 subjects were included in the analysis (228 men and 296 women; mean ± SD age, 87.8 ± 2.2 years; range, 85–102 years).

Oral Health Assessment

The comprehensive oral health assessment comprised a face-to-face interview including oral health–related quality of life (QOL) (Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index [GOHAI]), the ability to eat 15 items of food, a questionnaire regarding oral health behaviors, and dental examination by dentists (Iinuma et al. 2012). To identify behavioral risk factors, we have developed a 13-item oral health–related and hygiene-related questionnaire (Appendix Table). The questionnaire includes 4 items on denture hygiene practices modified from the study by Evren et al. (2011): frequency of denture wearing, frequency of denture cleaning, usage of denture cleanser, and denture wearing during sleep. These items were applied for 453 denture wearers only. Perceived swallowing difficulty was assessed with an item from GOHAI, “How often are you able to swallow comfortably?” After the interview, the dentist performed an oral examination to assess oral status, the presence of dental plaque, and gum inflammation according to the Standard of Dental Examination in School Health and Safety Act (Japanese School Dental Association 2007). Denture plaque was assessed using a modification of the Ambjørnsen Denture Plaque Index (Ambjørnsen et al. 1982). The presence of plaque on dentures was scored from 0 to 3 using the criteria proposed by Ambjørnsen, in which 0 is equivalent to no visible plaque, 1 is equivalent to plaque visible only by scraping on the denture base with a blunt instrument, 2 is equivalent to a moderate accumulation of dental plaque, and 3 is equivalent to an abundance of plaque. For 268 consecutive participants examined between April 2009 and November 2009, microbiological samples from the dorsal surface of the tongue were scraped 5 times with a sterilized cotton swab. The specimens were immediately inoculated onto special medium (CHROMagar Candida) for detection of Candida, according to a modification of the procedure of Wang et al. (2006).

Medical Assessment

At the same time as the dental examination, participants were interviewed and examined by trained geriatricians to assess medical conditions and medications, and to verify physical functional status (Barthel index). Cognitive function was evaluated according to the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). Nonfasting blood samples were obtained at baseline, and plasma concentrations of albumin, creatinine, and C-reactive protein (CRP) were measured using standard assay procedures. Plasma levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) were measured in duplicate using commercially available ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) kits (Quantikine HS [Human IL-6] and Quantikine HS [Human TNF-α], respectively; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Interassay coefficients of variation of IL-6 and TNF-α were 9.43%, and 8.72%, respectively.

Outcomes

The outcome of interest was a serious pneumonia event, which was defined as first hospitalization for or death from pneumonia. Participants were followed up for all-cause and cause-specific mortality and hospitalization from cancers, cardiovascular disease, pneumonia, falls and fractures, and other causes by telephone contact or mail survey conducted every 12 months. At month 36, those who remained in the cohort were examined according to the same protocol as the baseline survey, and any hospitalizations during the observational period were confirmed.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Baseline characteristics are expressed as means and standard deviations (SD) or as percentages. Continuous variables with a skewed distribution are described as medians (interquartile ranges [IQR]) and log-transformed for statistical analyses. We characterized denture wearing during sleep as either always (every night) or usually (5–6 nights/week). Differences in continuous variables at baseline were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. The chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables. For longitudinal analysis, we plotted Kaplan–Meier survival curves according to the risk strata. A prognostically significant result was defined as log-rank P < 0.05. We then used the univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards model to assess the relative risk of incident pneumonia. First, biological and behavioral factors known to be associated with pneumonia mortality (age, sex, education, smoking status, low body mass index [<18.5], history of stroke, respiratory disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors [ACEIs] and statins, and plasma levels of albumin, CRP, and IL-6) were calculated for hazard ratio (HR) in the univariate model; those with substantial associations (P < 0.1) were entered into the multivariate model. Because of the strong correlation between CRP and IL-6, they were entered separately in the model. Death from causes other than pneumonia was censored. In all analyses, P < 0.05 was taken to indicate statistical significance.

This research was approved by the Ethics Committees of Nihon University School of Dentistry (No. 2003-20, 2008) and Keio University School of Medicine (No. 20070047). The TOOTH is registered in the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN)-Clinical Trial Registry (CTR) as UMIN-CTR (ID: UMIN000001842).

RESULTS

During a 3-year follow-up period, 48 events associated with pneumonia (20 deaths and 28 acute hospitalizations) were identified, for an overall incidence of serious pneumonia of 3.1 per 100 per year. Seventy individuals died of other causes (cancer = 24; cardiovascular disease = 28; other causes = 15; and unknown causes = 3), 4 declined the follow-up survey, and 15 were censored at the time of last contact. The baseline characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. Those who developed pneumonia were more likely to have perceived swallowing difficulties, a habit of denture wearing during sleep, disability involving activities of daily living (ADL), cognitive impairment, lower body mass index (BMI), a history of respiratory disease and stroke, a lower level of albumin, and higher CRP and IL-6 levels. Neither remaining teeth, nor Eichner index score (Eichner 1990), nor medication intake showed any association with pneumonia.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants Who Did or Did Not Develop Serious Pneumonia during 3-Year Follow-Up

| Pneumonia

|

No Pneumonia

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | n = 48 | n = 476 | P* |

| Age, mean (SD) | 88.4 (2.5) | 87.8 (2.2) | 0.039** |

| Female, % | 45.8 | 57.6 | 0.128 |

| Higher education, % | 21.3 | 17.0 | 0.426 |

| Smoking, % | 44.4 | 38.7 | 0.523 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 20.6 (3.2) | 21.6 (3.2) | 0.122** |

| BMI <18.5, % | 25.5 | 17.3 | 0.166 |

| ADL disability, % | 36.2 | 25.4 | 0.120 |

| Cognitive impairment, % | 35.4 | 21.2 | 0.030 |

| Oral health status | |||

| Number of teeth, median (IQR) | 5 (0–12) | 7 (0–17) | 0.530** |

| Edentulous, % | 25.0 | 30.7 | 0.510 |

| Eichner index, %a | |||

| A | 8.3 | 9.8 | |

| B | 14.6 | 23.9 | 0.288 |

| C | 77.1 | 66.3 | |

| Swallowing difficulty, % | 21.3 | 12.0 | 0.105 |

| Gum inflammation, %b | 39.4 | 29.8 | 0.321 |

| Number of chewable foods, median (IQR) | 14 (13–15) | 15 (13–15) | 0.298** |

| Dental office visit in the past year, % | 60.4 | 59.7 | 1.000 |

| Denture hygiene practice (always or usually), %c | |||

| Frequency of denture wearing | 97.7 | 93.8 | 0.498 |

| Frequency of denture cleaning | 72.7 | 68.9 | 0.731 |

| Usage of denture cleanser | 32.6 | 33.6 | 1.000 |

| Denture wearing during sleep | 58.1 | 39.3 | 0.022 |

| Medical history, % | |||

| Respiratory disease | 45.8 | 32.1 | 0.076 |

| Stroke | 25.0 | 11.3 | 0.011 |

| Diabetes | 20.8 | 18.5 | 0.698 |

| CAD | 6.3 | 10.7 | 0.457 |

| Hypertension | 60.4 | 59.5 | 1.000 |

| CKD | 45.8 | 49.7 | 0.651 |

| Medications, %d | |||

| ACEI user | 2.2 | 4.6 | 0.710 |

| ARB | 26.1 | 29.3 | 0.735 |

| Statins | 10.9 | 16.5 | 0.402 |

| PPI | 19.6 | 13.7 | 0.270 |

| Histamine H2 blockers | 13.0 | 12.8 | 1.000 |

| Biochemical | |||

| Albumin, g/dL (SD)e | 4.0 (0.3) | 4.1 (0.3) | 0.047** |

| CRP, mg/dL, median (IQR)e | 0.15 (0.05–0.29) | 0.08 (0.04–0.17) | 0.011** |

| Interleukin-6, pg/ml, median (IQR)f | 2.08 (1.45–3.11) | 1.67 (1.29–2.44) | 0.030** |

| TNF-α, pg/ml, median (IQR)f | 2.48 (1.91–3.11) | 2.19 (1.88–2.79) | 0.116** |

IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; ADL, activities of daily living; CAD, coronary artery disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; CRP, C-reactive protein; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α.

In a multivariate Cox model, both swallowing difficulties and denture wearing during sleep were independently associated with an approximately 2.3-fold higher risk of incident pneumonia (for perceived swallowing difficulties, HR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.11–4.82; and for denture wearing during sleep, HR, 2.38; 95% CI, 1.25–4.56), which were comparable with the HR attributable to cognitive impairment (HR, 2.15; 95% CI, 1.06–4.34), history of stroke (HR, 2.46; 95% CI, 1.13–5.35), and respiratory disease (HR, 2.25; 95% CI, 1.20–4.23). To test the robustness of our results, we conducted a sensitivity analysis in which we excluded ADL disability from the multivariate model. We found a consistent association between denture wearing during sleep and incident pneumonia (HR, 2.35; 95% CI, 1.23–4.51). Another sensitivity analysis excluding those who died of causes other than pneumonia during the observation period (n = 70) demonstrated a solid association between denture wearing during sleep and pneumonia events in the multivariate model (HR, 2.37; 95% CI, 1.21–4.65; P = 0.012). None of the other denture hygiene practices or factors related to oral health status, including the number of remaining teeth, Eichner index, or use of denture cleansers, were significantly associated with incident pneumonia.

To gain mechanistic insight into the association between denture wearing during sleep and incident pneumonia, we examined baseline oral and denture status as well as systemic conditions in relation to denture habits (Table 3). Those who wore dentures during sleep were more likely to have tongue and denture plaque, gum inflammation, positive culture for Candida albicans, and higher levels of circulating IL-6 as compared with their counterparts. Thereafter, we incorporated each dental status item into the multivariate Cox model shown in Table 2, and we found that the associations between denture wearing during sleep and incident pneumonia were substantially attenuated and no longer statistically significant after further adjustment for gum inflammation or C. albicans (adjusted for gum inflammation, HR for overnight wearing, 1.45; 95% CI, 0.67–3.11; P = 0.344; and, adjusted for C. albicans, HR, 1.72; 95% CI, 0.66–4.46; P = 0.264), suggesting that the inflammatory and microbial burden of the oral cavity could provide a mechanistic link between denture wearing during sleep and incident pneumonia. The prevalence of ADL disability and coronary artery disease tended to be higher in nocturnal denture wearers than their counterparts; however, none of the systemic conditions had a significant impact on the relationship between denture wearing during sleep and incident pneumonia.

Table 2.

Hazard Risk from Univariate and Multivariate Cox Models for Incident Pneumonia

| Univariate Model

|

Multivariate Model

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | HR | 95% CI | P | HRa | 95% CI | P |

| Age | 1.12 | (1.02–1.24) | 0.024 | 1.09 | (0.97–1.21) | 0.146 |

| Sex (female) | 0.66 | (0.37–1.16) | 0.146 | |||

| Higher education | 0.92 | (0.50–1.67) | 0.773 | |||

| Swallowing difficulty | 1.98 | (0.99–3.99) | 0.055 | 2.31 | (1.11–4.82) | 0.025 |

| Denture wearing during sleep | 2.01 | (1.10–3.69) | 0.024 | 2.38 | (1.25–4.56) | 0.009 |

| Smoking | 1.22 | (0.68–2.19) | 0.516 | |||

| Cognitive impairment | 2.01 | (1.11–3.62) | 0.021 | 2.15 | (1.06–4.34) | 0.034 |

| ADL disability | 1.73 | (0.96–3.15) | 0.070 | 0.76 | (0.36–1.60) | 0.467 |

| BMI <18.5 | 1.59 | (0.83–3.06) | 0.166 | |||

| Stroke | 2.47 | (1.29–4.75) | 0.007 | 2.46 | (1.13–5.35) | 0.024 |

| Respiratory disease | 1.68 | (0.95–3.00) | 0.075 | 2.25 | (1.20–4.23) | 0.011 |

| Diabetes | 1.14 | (0.57–2.30) | 0.706 | |||

| ACEI user | 0.43 | (0.06–3.11) | 0.403 | |||

| Statin user | 0.61 | (0.24–1.55) | 0.300 | |||

| CKD | 0.87 | (0.49–1.53) | 0.625 | |||

| ALB (1 SD increase) | 0.74 | (0.56–0.97) | 0.027 | 1.05 | (0.75–1.46) | 0.790 |

| CRP (1 SD increase)b | 1.29 | (1.08–1.53) | 0.006 | 1.30 | (1.07–1.59) | 0.009 |

| IL-6 (1 SD increase)b | 1.37 | (1.07–1.75) | 0.013 | 1.20 | (0.92–1.58) | 0.186 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation; ADL, activity of daily living; BMI, body mass index; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; CKD, chronic kidney disease; ALB, albumin; CRP, C-reactive protein; IL-6, interleukin-6.

Table 3.

Oral Health Status and Behaviors According to Denture-Wearing Habit at Night

| Denture Wearing During Sleep

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes

|

No

|

||

| Characteristics | n = 186 | n = 267 | P* |

| Age, mean (SD) | 88.1 (2.8) | 87.7 (1.9) | 0.702** |

| Female % | 58.6 | 57.7 | 0.923 |

| Cognitive impairment, % | 25.8 | 21.3 | 0.308 |

| ADL disability, %a | 31.9 | 24.8 | 0.109 |

| Oral health status | |||

| Number of teeth, median (IQR) | 4 (0–10) | 6 (0–14) | 0.067** |

| Swallowing difficulty, % | 12.4 | 13.5 | 0.778 |

| Tongue plaque, %b | 42.2 | 32.5 | 0.046 |

| Gum inflammation, %c | 40.0 | 30.5 | 0.101 |

| Plaque adhesion, %c | 47.8 | 40.5 | 0.227 |

| Denture plaque, %d | 57.5 | 39.7 | 0.000 |

| Eichner index C, %e | 80.7 | 73.9 | 0.109 |

| Candida carriers, %f | |||

| Candida albicans | 57.8 | 43.4 | 0.025 |

| Candida tropicalis | 18.3 | 11.3 | 0.112 |

| Candida krusei | 22.0 | 19.5 | 0.646 |

| Total of 3 | 67.0 | 55.3 | 0.058 |

| Denture hygiene practice (always or usually), % | |||

| Dental office visit in the past year | 52.2 | 66.3 | 0.003 |

| Frequency of denture wearing | 98.9 | 92.9 | 0.002 |

| Frequency of denture cleaning | 63.4 | 73.8 | 0.022 |

| Usage of denture cleanser | 15.1 | 46.4 | 0.000 |

| Medical history, % | |||

| Respiratory disease | 31.7 | 32.6 | 0.919 |

| Stroke | 11.3 | 12.7 | 0.664 |

| Diabetes | 19.9 | 19.9 | 1.000 |

| CAD | 12.9 | 7.9 | 0.082 |

| Hypertension | 54.1 | 60.6 | 0.174 |

| CKD | 51.9 | 47.9 | 0.444 |

| Biochemical | |||

| Albumin, g/dL (SD)g | 4.1 (0.3) | 4.1 (0.3) | 0.776** |

| CRP, mg/dL, median (IQR)g | 0.10 (0.04–0.19) | 0.09 (0.04–0.19) | 0.924** |

| Interleukin-6, pg/ml, median (IQR)h | 1.81 (1.38–2.66) | 1.57 (1.25–2.27) | 0.017** |

IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation; ADL, activities of daily living; CAD, coronary artery disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CRP, C-reactive protein.

Articles from Journal of Dental Research are provided here courtesy of International and American Associations for Dental Research